DUKE: When I had graduated from the University of Wisconsin, Doug Stenberg, the head of Seven Hills at the time, put out a job notice through my college for a P.E. teacher position at Lotspeich. I contacted him and sent my resume. He ended up interviewing Marcia, as well as me, because the Lotspeich librarian position was going to be open the following year.

MARCIA: Our daughter, Jen, who later went to Seven Hills, was two at the time. I think Doug hired us because we brought Jen to the interview, and she was such a perfect toddler the whole time, so he thought, These two must be pretty good with kids.

DUKE: I got to Seven Hills the year of the merger, but being at Lotspeich, instead of in the high school, I missed all of the anxiety and the hard feelings that people felt. Just a few years before I got there, they had discontinued the Lotspeich Lions football team. When I first arrived, there was a shed packed with old football gear, shoulder pads, helmets. I think we just ended up throwing it all away.

I always wanted football at Seven Hills. I thought it would bring more students into the school, but it seems like I was wrong about that. We continued to grow during the years I was there. I thought it would bring more athletes who could help the other sports teams. We didn’t consider football right after the merger because we didn’t have enough boys. Once we started having bigger classes and more even girl-boy ratios, we started thinking about it. But Peter Briggs thought football wasn’t part of the school ethos, and there were Board members who didn’t want it.

Immediately after co-education, boys athletics struggled. But I think some of the boys felt like they were pioneers, and it gave them a chance to play when they otherwise might not have had the opportunity. One of my first years of coaching boys basketball in the Upper School, I called up Country Day to see if they would play us, and Country Day basically said, “No, you’re not good enough.” So, I went to Peter Briggs and mentioned it to him, and he wrote an editorial for the newspaper saying that Seven Hills wanted to play Country Day, and Country Day said we’re not good enough. I got a call from Country Day the day after the editorial ran, and they put us on the schedule.

I remember the game like it was yesterday, even though it’s been 40-something years. We were down by 10 with about two minutes to go. We tied it up with about 30 seconds left and went into overtime. Our boys were so excited that we had tied it up, and then I don’t think we scored a single point in overtime. Over the years, Country Day became a good rival.

A highlight for me was the first year we won the league basketball championship in 1990. I was the coach, and some of the players on the team were Craig Johnson, Pete Matthews, Craig Jones, Aaron VanderLaan. It was great because, remember, we’d gotten throttled over the years. One year, we lost a game to Summit 107-27. When we beat them to win the league championship, it was in their brand new gym. After we won, the kids poured the cooler of water over me. The water went all over the floor, so then we spent time after the game cleaning it up. It was worth it.

One of my philosophies as athletic director was that I wanted anybody who wanted to be on a team to be able to. The school adopted a “no cut” policy. In elementary and Middle School, you’ll get a chance to play. Once you hit Upper School, then it changes. We can’t guarantee playing time, but you can still be on the team.

The other driving philosophy was sportsmanship. I wanted our students to learn how to win with class and lose with class. It’s part of the character of the school, and part of being a good person in the world. In his senior year, I remember Grayson Sugarman had 99 goals for his soccer career, so he needed one more goal to make it a hundred. It was one of the last games of the year, he broke away, the goalie came out, Grayson flipped the ball over the goalie, went up to the goal line and then he passed the ball off to a teammate who hadn’t scored that year, and the teammate scored. Now that’s class.

Another important part of how we did things was that boys and girls athletics were always treated equally. Simple as that. That’s why we had games on Friday nights for girls teams, too, and when we started the cheerleading program, the cheerleaders cheered for both the boys and the girls teams. We’re one of the only schools that does that.

MARCIA: I loved that Seven Hills felt like a family. When Lotspeich burned down, it was during the summer of 1987, and we were home visiting family in Wisconsin. After getting the news, I remember shaking. And I remember thinking about how many books were lost. I thought, “We’re not going to have a library, so how will there be a librarian?” But I don’t think one person was let go because of budgets. The school carried on with the same excellence.

I worked the rest of that summer ordering books. When school started, the library was in a triple-wide trailer. I think I joked that at least with the overdue books that were still out, we had something to start over with. In the trailer, we had all of the book covers facing out on the shelves, because if we put them with the spines forward, it looked so empty. We started with 500, and, by the end of the year, we had 5,000 books.

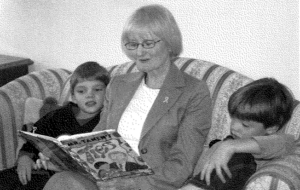

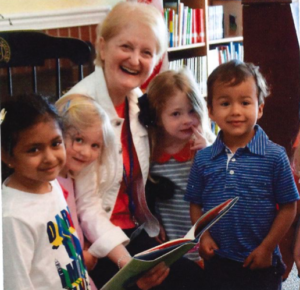

My favorite part of being Lotspeich librarian was reading to the kids. I would read something and say, “Oh, this is my favorite book,” and they’d say, “Mrs. Snyder, you say that about every book!” The school supported a yearly author or illustrator visit, and it was a pleasure meeting and introducing the students to a wide variety of children’s book authors. The library was meant to be a happy, relaxing place to choose something that you wanted to read.

DUKE: Marcia saying that Seven Hills is like family — that’s literally true for us. After we each spent more than 40 years at the school, our daughter-in-law, Sarah, now teaches at Lotspeich. Her mom, Judy Davis, was the language specialist at Doherty, and her aunt was Patti Guethlein. Our son-in-law, Pete Ceruzzi, is working in maintenance for the athletic department. Our daughter Kristen coaches Middle School volleyball, and our son John is now the school’s new chef.

MARCIA: We always said we’d be in Cincinnati for one year and then go back home to Wisconsin. But Duke loved his job, I loved mine, and now that’s carrying on to the next generation.

Click here to return to the stories page.