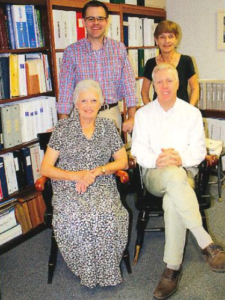

Peter Briggs

Peter Briggs was interviewed for this oral history in 2021; he passed away in 2022.

I had gotten out of the service in the Korean War, worked in undergraduate admissions at Harvard for 10 years, and then went to lead Western Reserve Academy in Hudson, Ohio. Seven Hills needed a head, so I came down and talked with people. The single person who influenced me the most was Charlie Meacham; he was a guy who could make anything work. I was impressed with the people I met — Helen Chatfield Black, Rosamond Wulsin, Lee Brewster.

In those days, there had been privileged families whose kids had gone away to boarding schools and that was starting to change. More of them decided to stay here in town. When a family like the Heads sent a child to Seven Hills, that made a statement.

My favorite thing about being headmaster was working with and being around the kids. Most of what I’d learn happened by walking around campus and stopping and saying, “What’s new?” to people. Sports were always very important to me. As a small school, I thought by not having football we could concentrate on other sports.

Twenty years is a long time to be the head of a school. I don’t remember everything, but we had strong students and teachers and alums. Assistant Head of School Susan Marrs was a giant. Former Head of Doherty Patti Guethlein was a star. Betty Goldsmith was a tower of strength and a driving force behind the creation of Books for Lunch and the Titcomb grants for faculty members to do things during the summer they’d always dreamed about.

When veteran independent school heads get together to swap stories, we talk about how dramatically the job changed over the length of our tenure. One of the happiest changes, I believe, was the integration of creative community service programs into the heart of our curriculum. I’m proud that our school felt compelled to teach students that meaningful contributions of their time, talent, and treasure to the common good is expected from these children and young adults to whom so much has been given.

I like to think the school grew in its reputation and popularity and diversity during my years there, and it means a great deal to know that I was appreciated.

LOUISE HEAD ON PETER BRIGGS

Peter Briggs was the best, and he arrived at a time when the school really needed him. If you had a complaint, he would spend so much time on it — he might check in and call you about it at least four or five times. So, you’d realize pretty soon, if you didn’t need Peter to call you four or five times, you would not complain!

SUSAN MARRS ON PETER BRIGGS

Peter loved connections and especially enjoyed keeping up with news of our graduates, so when he, former Upper School Dean of Students Jack White, and I were in Boston one year for the NAIS conference, he decided we’d drop in on one of our alums who was at Harvard, just to say hello.

He wrangled our way into Jason Cohen’s dorm by accosting a student coming out a side door in his characteristically uber-confident way, thrusting out his right hand to introduce himself with, “I’m Peter Briggs, and we’re looking for Jason Cohen. He lives here, right?” “Yes,” said the kid, a little bewildered. “Great! We’ll just go in here and find him.” And the kid opened the door to admit three strangers because no one ever said no to Peter on a mission.

With him in the lead, we began to climb the stairs only to encounter an incredulous Jason on the first landing. “Mr. Briggs!” he said, wide-eyed, before looking behind Peter to see “Mr. White!!” and “Mrs. Marrs!!!” He was stunned, of course. Who expects to see your high school teachers and Head of School marching up your dorm steps on a random Saturday morning? Peter then declared that we’d like to see Jason’s room and meet his suitemates. “OK,” murmured Jason, clearly wondering if this was really happening.

Once inside, Peter quizzed the other boys on where each one had gone to school, recalling a connection with headmasters at each one. And then came the most amazing moment: when he heard one boy’s name, looked at him carefully and heard his Boston accent, he said, “Is your father (naming the kid’s father), and did your grandfather have a bar in (naming the part of town)?” “Yes,” was the almost-whispered answer. Whereupon Peter, who’d worked in the Harvard Admissions Office after he’d graduated, barked, “I accepted your dad to Harvard!”

When we built the new Upper School, Bob Turansky was — how shall I say this — a very vociferous teacher. I think it was Susan Marrs who came to me and said, “When Bob’s teaching, we can’t turn down the volume he teaches at.” So, we needed to have a room that would be a Bob Turansky room — as soundproof as possible. We identified a room that we could tuck away a little bit. We double insulated the walls, double drywalled the walls, put sound abatement in the walls and in the ceiling so that if he was going off, the teacher next to him or even down the hall wasn’t going to be bothered. The architects and engineers said, “What are you doing here? You’re going to build this particular room for this one guy, and you’re going to spend extra money just so this one guy can teach the way he wants to teach?” and we said, “Absolutely!” And they said, “As opposed to telling him to pipe down?” and I said, “I’m not telling Bob Turansky to pipe down!”

When we built the new Upper School, Bob Turansky was — how shall I say this — a very vociferous teacher. I think it was Susan Marrs who came to me and said, “When Bob’s teaching, we can’t turn down the volume he teaches at.” So, we needed to have a room that would be a Bob Turansky room — as soundproof as possible. We identified a room that we could tuck away a little bit. We double insulated the walls, double drywalled the walls, put sound abatement in the walls and in the ceiling so that if he was going off, the teacher next to him or even down the hall wasn’t going to be bothered. The architects and engineers said, “What are you doing here? You’re going to build this particular room for this one guy, and you’re going to spend extra money just so this one guy can teach the way he wants to teach?” and we said, “Absolutely!” And they said, “As opposed to telling him to pipe down?” and I said, “I’m not telling Bob Turansky to pipe down!”

After the shot, there were different media interviews and former Athletic Director Brian Phelps let me do one in the Seven Hills gym. The TV reporter asked, “What are you doing with the money?” I said, “You’re looking at it. This is where we’ve put the investment — and it’s paying off.” Ultimately, all three of our boys went through Seven Hills and received college scholarships. That is return on investment.

After the shot, there were different media interviews and former Athletic Director Brian Phelps let me do one in the Seven Hills gym. The TV reporter asked, “What are you doing with the money?” I said, “You’re looking at it. This is where we’ve put the investment — and it’s paying off.” Ultimately, all three of our boys went through Seven Hills and received college scholarships. That is return on investment.